Barbara Lewis, Empowering Women through Healthcare

As part of Whitman-Walker’s 40th anniversary, officially January 13, 2018, we’re sharing 40 stories to help tell the narrative of Whitman-Walker in community. This week we bring you, Barbara Lewis! In 1972, Barbara worked with the Washington Free Clinic. She would later help start a weekly Lesbian Health Night for Whitman-Walker in 1979. Now a physician assistant at Whitman-Walker, Barbara celebrated her 20th anniversary as an employee this past March 2018! Barbara shares her journey and perspective on the history of Whitman-Walker, as well as how her work in lesbian and women’s health inspired aspects of the care we provide today.

Click the orange play button below to hear Barbara’s August 17, 2017 oral history – a recorded interview with an individual having personal knowledge of past events. Thank you to the DC Oral History Collaborative for supporting the collection of this oral history.

On Feminism & Empowering Women in Healthcare:

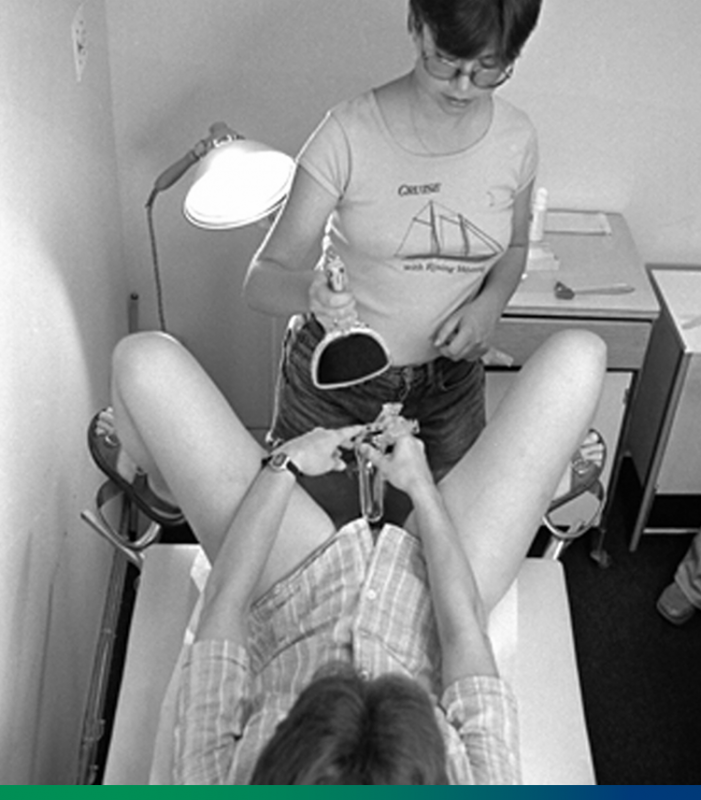

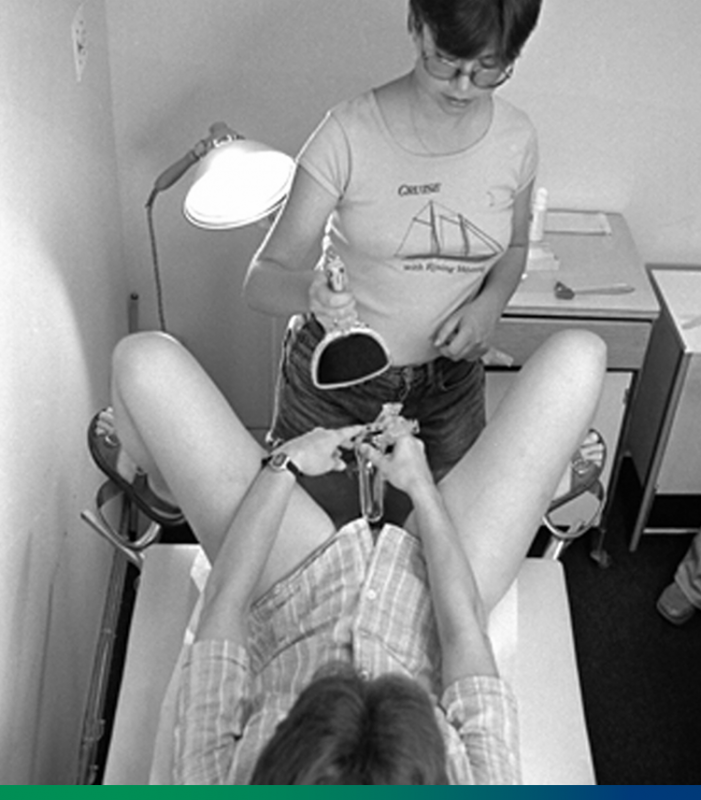

“We rented an apartment; it was part of some group house. We also were able to go up to Elk, California, which is up three hours north of San Francisco in Mendocino County and stay on the ocean. These friends had rented a house up there for weekends, and we were able to go out there during the week when they weren’t there. I spent time up there. During that time; that was a very influential time for me because Jim had been in SDS, which was the Students for Democrats, and he was fairly radical. It was the beginning of feminism; the second wave of feminism – the first being the Suffragettes. The second wave was in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s. He was really encouraging me to be a feminist, and he was suggesting that I start doing some reading. I started reading people like Kate Millett and Shulamith Firestone, which were feminist writers in the early 1970s, ’71. I also went to the Berkeley Women’s Health Collective because I thought I had a vaginal infection. It was there that a young woman who was my age did my exam and then showed me the organisms under the microscope. That was really eye opening because up to that point most of my exams had been done by male gynecologists, and here was somebody that was my peer that was actually doing the exam, and she didn’t have any particular degree. This was the beginning of this movement of women empowering themselves. So, that had a big influence on me.”

On Her Start at the Washington Free Clinic:

“Well, when I came back from Berkeley, I heard about the Washington Free Clinic and I heard that they were reorganizing. Somebody just told me about it, that they had been a clinic; it was started in 1968. A lot of runaway people, hippies running away from home, or just a lot of nomadic young people just traveling around and needing a place for healthcare. So, the free clinics started. Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco was the very first one. Again, it was the flower power children and the hippie culture. So, they started a similar thing in Washington at this church. I heard they were reorganizing and they were having this community meeting to talk about it. When they had this community meeting, I went. I had all these ideas now that I had brought back from the Berkeley Women’s Health Collective about women’s health. I kind of stood up and talked about it, and talked about how I was really interested in starting a women’s health collective and starting to do empowerment for women. People got very interested in my ideas and asked me if I’d be interested in being part of this collective to run the Washington Free Clinic. It turned out that I said “sure” because I didn’t really have a job. Six of us formed this group and we got elected by this community meeting to run the clinic, which in the past had been run by one person. We actually got a salary, very small, but very subsistence – I think it was $75 a week – to be running the clinic.”

On the First Time She Heard about HIV:

“Whitman-Walker asked us to come and to start a Lesbian Health Night, which we did. This was the very first incarnation of Whitman-Walker, which was at 17th and Q Street. We started in ‘79 and we had a Wednesday night clinic. We started there doing women’s health, and also did lesbian health, and resource collective and mental health there as well. Somewhere after ’79 we moved over to 18th Street at Belmont, where Whitman-Walker had moved. It was there that on Wednesday nights that I noticed on the bulletin board downstairs where our lab area was that there were clippings – newspaper and magazine clippings – that talked about these gay men in San Francisco who were starting to get cancerous lesions on their bodies, and pneumonia. This was about 1981. They didn’t have a name for it, but they were starting to see a trend. This was my first awareness. All this time I was actually working in the emergency room at Howard. I was still working there full-time. But, my first awareness of HIV was not at Howard; it was really on the bulletin boards at Whitman-Walker.”

On Receiving the Gene Frey Award for Volunteerism:

“I got nominated for this award. At that time, there was a lot of money coming into Whitman-Walker for HIV disease. We had these big dinners, these big award dinners. Gene Frey was someone who had died of AIDS and he had been somebody who had volunteered and done a lot of work at Whitman-Walker as a volunteer in the male community. We had these real huge award dinners that were at hotels. This was like at the Washington Hilton. I think this one was at the Sheraton Woodley Hotel that is now something else. But there was a lot at the Omni Sheraton. There were a lot of different hotels that had these big – I mean, really, there would be like 1,000 people at these big dinners at tables, kind of like the Human Rights Campaign dinners, and there was a lot of money that came in to support HIV so they had these big celebrations to support everybody who worked or volunteered. There were staff awards and there were volunteer awards. I’d gotten nominated for a volunteer award because both I worked in lesbian health and I worked in HIV. I did both. I remember what happened, and the reason I bring this up is because what I was saying is that communities were so separate in a lot of ways, but most of the lesbians I know became really, really concerned about HIV, and people really wanted to do something to help men that were dying from HIV disease; ‘cause the women were not; at least lesbians were not. Certainly there were straight women that were being infected, but not lesbians. I think a lot of us felt really compelled to do some work now for gay men. In fact, there was a plaque that was in the old pharmacy at ET – The Elizabeth Taylor Center – that had the lesbian honor roll. I don’t know if you ever saw that, but there was a plaque. I don’t know where that plaque went, but on it are all the names of lesbians who did volunteer work for HIV disease, and they called it The Lesbian Honor Roll.”

On Lesbian & Women’s Health:

“I was also concerned about lesbian health. Of course, lesbian health and women’s health at Whitman-Walker was kind of low on the totem pole because all the money was coming in for HIV. So, no money was coming in, really, for lesbian health and issues like that. We actually got to give a little speech. I remember saying, as much as I was committed and caring about men in our community and people dying with HIV and AIDS, but I wanted to put a challenge out to my gay brothers to also give some time and energy into women’s health issues such as breast cancer. Specifically I said that because Audre Lorde, who was a well-known lesbian writer, had just died of breast cancer. So, we thought that our issues were also important at Whitman-Walker and we wanted them to be addressed and we were hoping that we would get support from gay men for those issues the same way that we were giving them support for HIV disease.

Now, if you want to ask me about lesbian stuff, I could have a different opinion about that because, again, I feel like women are sort of always at the bottom of the barrel. I feel like that lesbian health and women’s health kind of always don’t take as much precedence as health with men’s health, and maybe even transgender health. I think transgender has kind of moved to the top of the food chain type thing. Then, gay men’s health; and then women’s health and lesbian health is kind of the bottom of the barrel. It’s always felt that way. So, I’ve always felt that we kind of got crumbs, a little bit, about that. That is what I would say to that. But, HIV is always at the top.”